The Sad Reality About Sleep In The Transportation Industry

Courtesy of Huffington Post by Amanda L. Chan: The engineer who was at the controls of the Metro-North train that derailed in the Bronx on Sunday may have fallen asleep while he was helming the train, according to news reports.

Courtesy of Huffington Post by Amanda L. Chan: The engineer who was at the controls of the Metro-North train that derailed in the Bronx on Sunday may have fallen asleep while he was helming the train, according to news reports.

DNAinfo reported that William Rockefeller “all but admitted he was falling asleep” as he was commandeering the train, and then woke up before turning the curve where it ultimately derailed. At that point, the train was going 82 miles per hour (the curve called for speeds of 30 miles per hour).

The train trip started at 5:54 a.m., leaving from Poughkeepsie and heading for New York City. DNAinfo pointed out that sources say there is no obvious reason for Rockefeller to have fallen asleep, as “they had no initial reason to believe he had been overworked or was out late the night before.”

The New York Daily News reported that Rockefeller was well-rested at the time of the incident — “there was every indication he had time to get rest, to get focused,” Earl Weener, of the National Transportation Safety Board, told the Daily News — but that he had just two weeks ago been moved to work the 5 a.m. shift after years of working the afternoon shift.

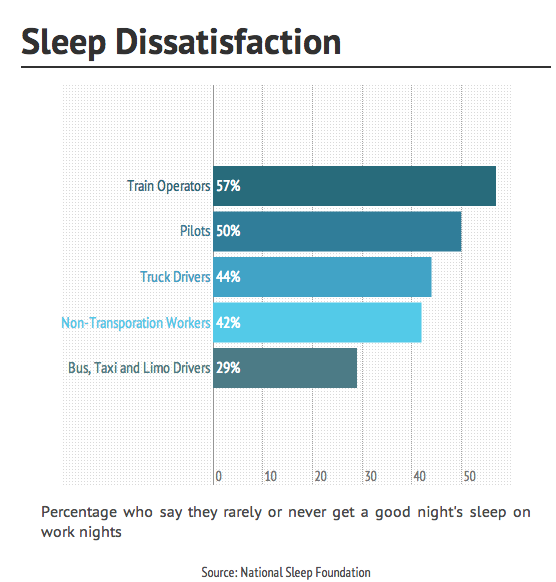

Looking at the statistics, train operators are actually one of the most likely groups to experience sleep-related job performance issues. The National Sleep Foundation conducted a poll of 800 transportation workers and 300 non-transportation workers, asking whether sleepiness affects job performance at least once a week. Train operators were the group most likely to admit this, at 26 percent, followed by pilots, at 23 percent. Meanwhile, just 17 percent of non-transportation workers reported that sleepiness affected job performance in the last week.

“For transportation workers, it’s a 24-hours-per-day industry, which means there are always going to be people working under shifts that are not conducive to getting adequate sleep,” Thomas J. Balkin, the chief of the department of behavioral biology at the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research and chairman of the National Sleep Foundation, previously told HuffPost. “Unfortunately, the nature of the work makes it very dangerous to be sleepy.”

On its own, sleepiness can already affect job performance by taxing the brain, leading to decreased abilities to rationally think, make sound decisions and perform tasks. And behind the wheel, sleepiness affects the ability to pay attention and safely operate a vehicle. Coupled together, it’s no wonder sleep (or lack thereof) can lead to so many safety issues on the job, particularly in transportation industries.

Indeed, the National Sleep Foundation poll showed that 18 percent of train operators has made a serious error on the job due to sleepiness. Twenty percent of pilots and 14 percent of truck drivers admitted the same. These workers are also more likely than non-transportation workers to be involved in a car accident due to drowsiness while commuting to and from their jobs.

Train operators were also the most likely of the transportation workers in the survey to report not getting a good night’s sleep during work nights, with 57 percent reporting this dissatisfaction.

Sleep Dissatisfaction | Create infographics

The construct of their jobs may not be helping matters. Nearly half of train operators — 44 percent — said that because of the way their work schedules are structured, they are unable to get adequate sleep each night. Only 47 percent of train operators said they work the same schedule every day, compared with 76 percent of non-transportation workers, and the average amount of time between shifts for train operators is 12.5 hours, compared with 14.2 hours for non-transportation workers.

Sleep problems — specifically obstructive sleep apnea — have been under the microscope in recent years in the flight and trucking industries, in particular. Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a sleep disorder that involves pauses in breathing during sleep, leading to disturbed sleep and daytime fatigue. The Federal Aviation Administration announced just last month that it would soon require all severely obese pilots (with a body mass index of 40 or higher) to undergo sleep apnea screening, and that if diagnosed, they would be required to undergo treatment before receiving their medical certificate.

“OSA is almost universal in obese individuals who have a body mass index over 40 and a neck circumference of 17 inches or more, but up to 30 percent of individuals with a BMI less than 30 have OSA,” Dr. Fred Tilton, M.D., the Federal Air Surgeon, wrote in an editorial announcing the new policy.

Obstructive sleep apnea is notorious among truck drivers as well, with statistics from the U.S. Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration (FMCSA) indicating that nearly one-third of commercial truck drivers have the condition. A recent study also showed that 41 percent of Australian commercial truck drivers had the condition.

However, not everyone with sleep apnea may be accurately reporting its effects. A study presented at a recent meeting of the European Respiratory showed that underreporting of daytime sleepiness was more common among commercial vehicle drivers than non-transportation workers.

Right now, the FMCSA says that if you have a condition that could impair ability to drive safely — which, while not identifying sleep apnea specifically, would encompass that condition — you are not medically qualified to drive commercially interstate. But “once successfully treated, a driver may regain their ‘medically-qualified-to-drive’ status. It is important to note that most cases of sleep apnea can be treated successfully,” according to the FMCSA. (Determinations on what makes a person “medically-qualified-to-drive” differ by state.)

However, in October, President Obama signed a bill that would begin the data-collection process for developing rules particularly for sleep apnea in commercial truck drivers, The City Wire reported.

In general, commercial truck drivers are not allowed to work more than 70 hours a week, and must take a break before driving again if they just worked an eight-hour shift, according to a recent rule by the Department of Transportation.

While transportation workers are more likely to report sleep-related job problems, drowsy driving is pervasive among non-transportation workers, too. After all, the National Sleep Foundation poll also found that about one in six people in non-transportation fields experiences job performance issues due to sleepiness at least once a week.

Aside from drivers and vehicle controllers, there are some jobs that may be detrimentally affected more by sleepiness than others. Rules have been passed to help ensure air traffic controllers, for instance, are more well-rested while on the job. In 2011, the FAA announced changes in scheduling for air traffic controllers so that they would have more time to rest in between shifts, giving them at least nine hours between shifts (previously they had eight). The rules also mean they cannot switch shifts unless there’s been nine hours, at least, between their last shift and their next shift.

“We expect controllers to come to work rested and ready to work and take personal responsibility for safety in the control towers. We have zero tolerance for sleeping on the job,” Ray LaHood, the Secretary of Transportation at the time the rule was passed, said in a statement. “Safety is our top priority and we will continue to make whatever changes are necessary.”

Doctors are another class of workers who could make an especially life-changing mistake from drowsiness. In 2011, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education enacted rules that would limit medical interns (first-year residents) to working 16-hour shifts. However, second- and third-year residents still can work 28-hour shifts, Kaiser Health News reported. An article published that same year in the journal Nature and Science of Sleep argued that less sleep is only harmful — for both the residents and the patients — and that the limits on 16-hour shifts shouldn’t just apply to first-year residents.

Shift work — whether it’s by doctors, or by factory workers or restaurant workers — has been linked with a number of health problems besides sleep problems, including heart disease, depression, diabetes and gastrointestinal disease, the National Sleep Foundation noted. It’s also been shown in some studies to raise risk of cancer.

Like many things, sleep may be predicted by the job you have and the money you make. For instance, a survey from Britain’s Sleep Council showed that more people earning the equivalent of $116,000 or more a year slept “very” or “fairly” well most nights, than those who just made the nationwide average.

And some fields seem to be more plagued by sleeplessness than others. A study, based on analysis of Centers for Disease Control data by the company Sleepy’s, showed that forest/logging workers actually get the best shut-eye — sleeping for an average of seven hours and 20 minutes a night — while home health aides are the most sleep deprived — getting an average of six hours and 57 minutes of sleep a night.

Category: Featured, General Update